January 5, 2019

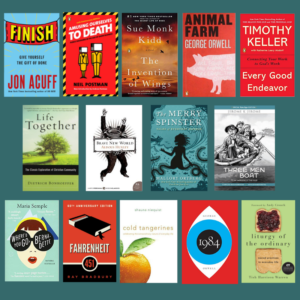

- Finish: Give Yourself the Gift of Done by Jon Acuff {a} (2017, nonfiction/motivation) – This was the first book I’ve read by Jon Acuff and I loved it. He read the audiobook himself which was fun because he occasionally interjected things that weren’t in the printed version of the book, but even without those interjections this book is a great one. It was funny and inspiring, and was a really good kick in the butt for me.

- Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business by Neil Postman {a} (1985, nonfiction) – This book is a classic that’s only becoming more and more important as technology marches on. It would be hard to disagree with Postman’s overall premise that our addiction to television (and screens in general, now) has changed us — individually and culturally — for the worse. For those of us who think that we’re so informed and superior now in our modern age, we’d do well to note the mental stamina of those who’ve come before us — Postman gives examples of presidential debates that drew enormous crowds of ordinary folks to listen to speeches that lasted for hours each. (By comparison, the final debate of this last presidential election cycle had each candidate speaking for two minutes at a time. Two.) He looks at the difference between knowledge we must to work to gain (through reading) and knowledge we don’t have to work to gain (by watching), and he critiques our tendency to gather little snippets of information when we’re watching the news and then think that we understand the big picture. All of these ideas are important and well-reasoned. My only complaint about the book is that Postman sometimes comes across as not just concerned but downright curmudgeonly. His views towards photography, in particular, seemed strange to me — he speaks about photography in deprecating tones for reasons I can’t quite comprehend. You kind of get the impression that if he’d been around in 15th century Germany, he’d have been picketing outside Gutenberg’s printing press, lamenting the loss of the oral tradition. (I think this is partly due to the fact that I listened to the audiobook — the reader’s voice is more than a little Eeyore-ish, and maybe he read the bits about photography with more sarcasm in his tone than the author intended.) Anyway, many other authors have taken up Postman’s cause in recent years as well — last year I read The Vanishing American Adult, in which Ben Sasse frequently references Postman’s book and then fleshes the ideas out even further but with a contemporary perspective, and this year’s The Tech-Wise Family took a similar perspective.

- The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd (2015, historical fiction) – When it comes to telling stories from varying first-person perspectives (which seems to be the only way anyone will tell a story anymore), I think Sue Monk Kidd has done a better job than most with this book. It seems like many authors have a hard time capturing multiple voices in a way that actually lends distinction to the characters, but she did. I thought this was a very poignant look at the circumstances that would have influenced each of these women in the south in the early nineteenth century, and the fact that it’s based on a true story (albeit loosely) made it even more of an enjoyable read. Save time for the author’s end-notes on this one, because they were pretty interesting too.

- Animal Farm by George Orwell (1945, fiction/satire) – A quick read, much quicker than 1984, and it makes essentially the same points about the dangers of socialism, dictatorships, and our own unfortunate tendencies to just go with the flow and hope for the best when things begin to go terribly wrong.

- Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work by Tim Keller (2014, nonfiction/religious) – This is the second book I’ve read this year about the sanctity of work and the idea that from the beginning, God created us for work. Looking at it from a biblical perspective, there was work in the garden of Eden even before sin entered the world. Work, like everything else, was impacted by sin, but in and of itself work is a good thing, not a cursed thing. I think this was a great book, especially the introduction and the last few chapters, but it felt a little tedious in the middle, and I might actually recommend Jordan Raynor’s Called to Create (see number six in Part One) over this one (although Timothy Keller is usually one of my favorites).

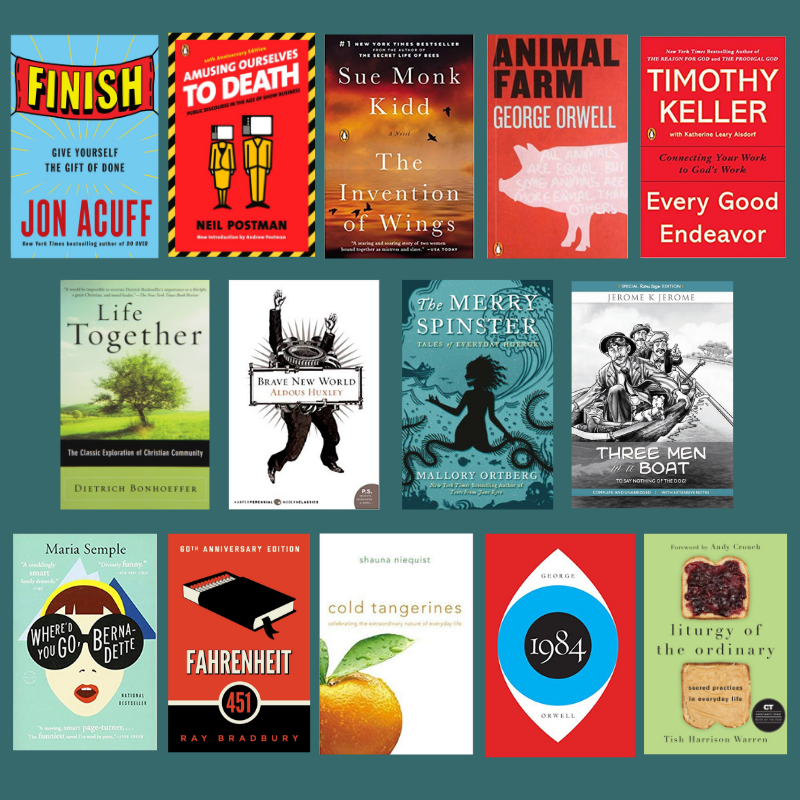

- Life Together by Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1939, Christian living) – After reading about Dietrich Bonhoeffer earlier this year (number three in Part One), I wanted to finally read something by him. He wrote this little book while working with an underground seminary in 1938, and it has all the passion of a man who desperately wanted to see the church reflect Christ rightly in evil times. The first two chapters of the book talk about how we structure our day as believers and frankly, they come across as a bit legalistic, BUT the final three chapters are deep and beautiful and convicting and powerful. He talks a lot in those chapters about how we view ourselves in relation to each other and in relation to God, and in spite of all his German methodicalness of thought (which comes across as a bit heavy-handed in those first couple chapters), there’s a poetry to the way he talks about humbling ourselves and seeing the beauty of God’s creative design in one another that brought me to tears.

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley {a} (1932, dystopian fiction) – In 2018 I read Brave New World, Fahrenheit 451, and Animal Farm and 1984 (both by George Orwell). There are lots of fun discussions out there as to which of these books most closely represent where we are today. I lean towards Orwell, but Postman (see number two above) leans towards Huxley, and references BNW many times in his book. The most important concept in this book is the the idea that people are more easily controlled by comfort than by oppression, an idea which should spur us to consider what our own various forms of “soma” are that offer relief from discomfort but also distract us from things that we probably ought to be paying attention to. But I don’t love this book, even though I agree with that overarching idea. The characters are all terribly boring, including John the Savage who, as the one character who has free will, ought to provide a more lively counterpoint to the rest of the bland and homogeneous cast. Also, I don’t think a world that encourages over-consumption would result in the clean, pristine, healthy version of London that BNW portrays. (Incidentally, I think the disgusting, trash-covered world populated by lazy slobs in the movie Idiocracy is maybe a better picture of where over-consumption can lead.) Additionally, I couldn’t shake the feeling all the way through that maybe Aldous Huxley didn’t actually see this imagined future as a bad thing. Anyway, if you’ve never read this book, you really ought to, but read it for the ideas, not for the story-telling.

- The Merry Spinster by Mallory Ortberg (2018, fantasy) – Ew. Just….no. Mallory Ortberg wrote Texts From Jane Eyre, a book that makes me laugh until I cry. Ortberg also wrote all the Two Monks posts at The Toast, which also make me laugh until I cry. This book of twisted fairy tales did NOT make me laugh until I cried. It very nearly weirded me out until I cried….but it couldn’t even pull that off. These stories are just strange — kinda creepy but not actually scary, and they don’t make any discernible points. Ortberg’s main strategy for adding a dark undercurrent was to turn one or more characters from each story into sociopaths, and they were all just murky and strange. I’d finish one, say “huh,” then start in on the next, hoping to enjoy it more, but the enjoyment never came.

- Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) by Jerome K. Jerome {a} (1889, fiction) – You know when you’re planning a trip down the river with a couple of your pals, and every little teeny-tiny detail of your adventure spurs a hilarious flashback of some sort? Yeah, Jerome K. Jerome gets it. In fact, he wrote a whole book about it. It’s a book that’s quite old, but the humor is surprisingly fresh. There are several audio versions out there, but I insist that you listen to the one narrated by B.J. Harrison, because he is fabulous.

- Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple (2013, fiction) – Ohhhhhh, I love Bernadette. You know how I said that well-formed characters trump a well-formed plot (in my review of The Nightingale in Part One)? And you know how I said that it seems like all modern fiction wants to tell stories from alternating first-person points of view (in number three above)? Thank you, Maria Semple, for giving us a little something different to sink our teeth into. Bernadette is a GREAT character, as are most of the others in this book, and while the book is first-person-ish, Semple strayed away from that tired-and-typical format that’s standard these days (chapter 1 – character A, told in first person; chapter 2 – character B, told in first person; chapter 3 – back to character A; etc. forever). Bernadette’s story is told through some narration plus a collection of letters, emails, and other scraps of paper collected by her 15-year old daughter Bee, and I knew I loved this author when a hospital receipt made me laugh out loud. This book is worth the read.

- Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1953, dystopian fiction) – This one doesn’t hit too close to home (as compared to Orwell’s and Huxley’s books, see above and below), but there are two things that do: 1) the obsession with “reality” TV, and the distance that creates in actual relationships; and 2) the idea that people should never have to be offended by others. That’s what really stuck out for me, given our current culture of offense. The desire to never offend anyone was given as one of the reasons for burning books, and it was also used as a way to maintain separation between people, because in this story no one would ask each other any kind of probing question at all for fear of causing offense. That last bit is more than a little like us. (In fact, I once wrote a whole blog post about our fear of offending each other.) Anyway, in the book this turned everyone’s attention increasingly inward, and made them more susceptible to control. Like Brave New World, I think this is worth reading if you haven’t before. When reading it, try to get your hands on a copy that includes an introduction by Neil Gaiman, which is short but good (the version I linked has it).

- Cold Tangerines by Shauna Niequist (2010, memoir) – I’ve read snippets of other Shauna Niequist books, but this is the first one I’ve read straight through, and all through the book I couldn’t decide whether she and I would be completely kindred spirits, or not kindred at all. She has an intensity that is very different from me but a dedication to finding God’s purpose in her life that I very much relate to. Mostly I really really like her and her way of seeing beauty in the ordinary and holiness in the humble, and I want to live with the same kind of intentional way of seeing God’s hand at work in the world and in my life.

- Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell {a} (1949, dystopian fiction) – Unlike Brave New World, this book envisions a future in which we’re enslaved by oppression rather than by comfort. The ideas of thoughtcrime, Newspeak, Big Brother, and doublethink — which all find their origins here in this story — are unnerving because they feel far closer to reality than to science fiction, but the elimination of comfort and pleasant experiences as a means of control does not hit as close to home. As a story, I enjoy this one more than Brave New World. I don’t love it, but once again I do think it’s worth reading if you haven’t before. However, if you’re curious about Orwell’s ideas, Animal Farm is a much shorter read and communicates many of the same ideas.

- Liturgy of the Ordinary by Tish Warren (2016, Christian living) – As a mom, whose life often feels full of very ordinary things, this book came like a breath of fresh air for me. The author takes us through the many demands of a typical day, from waking up to making the bed to taking care of our hygiene to interacting with our children, our spouses, our jobs, our churches, and the world at large, and points us to the ways every one of those things can become an opportunity for worship. For the Christian, no action is divorced from our faith, and there can be joy even in the sometimes tedious things I must do each day because they all point to my need for the Lord and his gracious provision for me. I underlined many things in this book, but this excerpt kind of sums it up: “[My bed making ritual] teaches me to slow down, to bravely enter a dull Tuesday morning, to embrace daily life, believing that in these small moments God meets us and brings meaning to our average day. We are not left like Sisyphus, cursed by the gods to a life of meaninglessness, repeating the same pointless task for eternity. Instead, these small bits of our day are profoundly meaningful because they are the site of our worship. The crucible of our formation is in the monotony of our daily routines.”

Thanks for reading! Look for the third (and final!) section soon!

2018 Book Review – Part II

Be the first to comment